Water vendor / Kiosk

The “re-discovery” of water vending was spurred by studies of willingness to pay for water. Indeed, the premium on vended water shows a willingness to pay for water that flies in the face of the claim that people believe water is a free good, which should not be bought and sold. This has been one argument for the increase of water tariffs and the capitalization of private initiatives in the water sector. Water vendors have been praised for their entrepreneurship, as well as their ability to reach the poor and areas that are difficult to develop with conventional infrastructure. At the same time, they are still often scorned for exploiting people’s absolute and basic need for water.

The understanding of, and interest in, water vendors remains minimal, however, when viewed in light of the vast amounts of research and the heady controversy that has surrounded private sector participation in the piped-water systems, and the involvement of multinationals in particular. Small vendors are already providing water services to a large share of the world’s poorest urban dwellers, often in the face of official discouragement. Private utility operators are less significant, and it is not clear that they will be interested in serving more than the small fraction of urban poor living in the vicinity of the large piped-water networks. Better services from water vendors may still be considered inadequate by international standards, but are there cases where such services could yield a substantial improvement in the well-being of urban dwellers? If so, can the urban poor, and those who claim to want to help them achieve improved water and sanitation services, afford to ignore them?

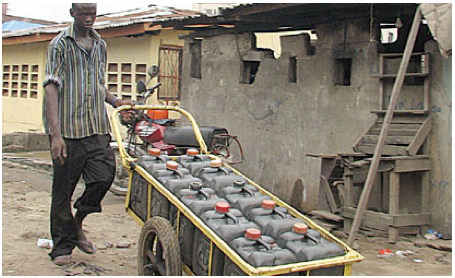

Water vendors may operate water kiosks, where they sell water from a shallow well, a borehole, a commercial water connection, or a household connection to the piped network. Consumers may carry the water to their homes themselves. Distributing vendors may also collect water from kiosks. They typically carry water in containers loaded on bicycles, hand- pushed carts, or even animal-drawn or motorized carts, and bring it to households and small businesses. On a larger scale, and often serving higher-income customers, there are water tanker trucks that carry greater quantities to premises with larger storage capacities.

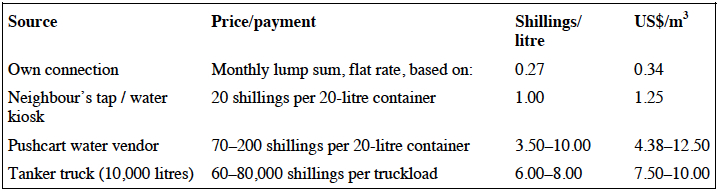

Costs

Field experiences

A pushcart water vendor in Manila (Philippines)

“The water vendor starts work each day at 3:00 a.m., 7 days a week. He buys water from the concessionaire at 1 peso per 16-liter container and distributes it by pushcart (a bicycle with a large sidecar) to 20 customers, living an average of 2 kilometres from the source. He sells 40 containers per day at 5 pesos per container... He pours water from his containers to his customers’ containers when he delivers. Working an 84-hour week, he earns 5,000 pesos per month, whereas the poverty line is more than 9,000 pesos per month. He has a family of five to support. He says his biggest problem is always money, and he receives no tips and no year-end bonus. It is surely a tough job pushing water with little reward. Still, he has been a water vendor for 9 years.”

Women water vendors in Honduras

United by their collective need for reliable and affordable water and the burden faced from high water prices incurred by private vendors, women in low-income urban neighbourhoods throughout Honduras have developed and managed their own licensed water-vending stations. The project benefits include lower and fixed water prices and the provision of part-time employment for poor single women with children.

Reference manuals, videos, and links

- Lagos: Water everywhere but none to drink. Vanguard (online edition).

- Many Leaks Yearning for Plugs in Nigeria's Water Sector. Pulitzer Center on crisis reporting. 2011.

Acknowledgements

- KJELLÉN, MARIANNE AND MCGRANAHAN, GORDON. INFORMAL WATER VENDORS AND THE URBAN POOR. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), 2006.