Difference between revisions of "Centralized treatment"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Image:plant Iraq.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In 2007, over 3,000,000 people benefited directly from the [http://www.icrc.org/eng/index.jsp ICRC’s] repairs, renovations and upgrades of water storage and delivery systems in Iraq, Basra. Here, they are renovating a water-treatment plant. Photo: [http://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/photo-gallery/photos-water-habitat-170308.htm © ICRC / irak.]]] | [[Image:plant Iraq.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In 2007, over 3,000,000 people benefited directly from the [http://www.icrc.org/eng/index.jsp ICRC’s] repairs, renovations and upgrades of water storage and delivery systems in Iraq, Basra. Here, they are renovating a water-treatment plant. Photo: [http://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/photo-gallery/photos-water-habitat-170308.htm © ICRC / irak.]]] | ||

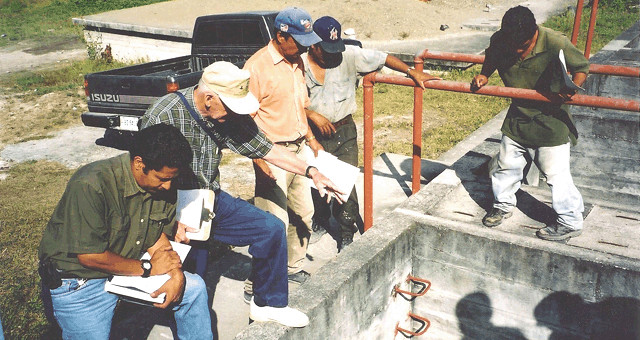

| − | [[Image:water treatment plant2.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In 2001 CESO Adviser Jake Dick travelled to Santa Rosa de Copan, a city nestled in the western mountains of Honduras, to restore an abandoned water-treatment plant to functionality. <br>Photo: [http://www.ceso-saco.com | + | [[Image:water treatment plant2.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In 2001 CESO Adviser Jake Dick travelled to Santa Rosa de Copan, a city nestled in the western mountains of Honduras, to restore an abandoned water-treatment plant to functionality. <br>Photo: [http://www.ceso-saco.com Ceso/Saco.]]] |

| − | + | ||

In this strategy, the population is supplied with drinking water from large, centralised water treatment plants. The treated water is piped to all the communities in the geographical area served by the treatment plant, thus requiring an extensive pipe network, so as to reach even the most remote communities. The treatment plants could be managed and operated by the larger municipalities or, more likely, by the Water Boards in that region. Generally, these plants should be well managed and operated effectively due to availability of sufficient O&M funds and qualified human resources. | In this strategy, the population is supplied with drinking water from large, centralised water treatment plants. The treated water is piped to all the communities in the geographical area served by the treatment plant, thus requiring an extensive pipe network, so as to reach even the most remote communities. The treatment plants could be managed and operated by the larger municipalities or, more likely, by the Water Boards in that region. Generally, these plants should be well managed and operated effectively due to availability of sufficient O&M funds and qualified human resources. | ||

Revision as of 22:11, 6 January 2017

Photo: Ceso/Saco.

In this strategy, the population is supplied with drinking water from large, centralised water treatment plants. The treated water is piped to all the communities in the geographical area served by the treatment plant, thus requiring an extensive pipe network, so as to reach even the most remote communities. The treatment plants could be managed and operated by the larger municipalities or, more likely, by the Water Boards in that region. Generally, these plants should be well managed and operated effectively due to availability of sufficient O&M funds and qualified human resources.

However, implementation of large and centralised drinking water treatments in developing countries is highly unlikely due to investments, civil construction, maintenance of infrastructures and availability of chemicals that are required. As a consequence, people in many developing countries are forced to consume water directly from natural sources or apply household water treatments as chlorination, solar disinfection or boiling, that have low cost but variable effectiveness.

Centralised water treatment and a piped distribution network have had a mixed history primarily due to high initial costs and operation and maintenance, inadequate access to training, management and finance sufficient to support a fairly complex system for the long term. These complete systems are also slow to be implemented so waterborne disease continues in the interim.

Construction, operations and maintenance

Comparing centralised plants with decentralised plants

For the rural stand-alone treatment plants (decentralised plants), the type of technology employed has a marked effect on the sustainability of the treatment scheme. The tendency is more towards low-tech technologies requiring minimal operation and maintenance inputs. The reason is the lack of skilled and trained personnel to operate and maintain the plant, poor access roads in the deep rural areas hampering delivery of chemicals and equipment, and management challenges resulting from the remoteness of these rural plants.

As such, Slow sand filters are often used in the rural areas, but even these plants present challenges with operation and maintenance, and the treatment is often compromised by these challenges. The concept of using automated high-tech technologies has gained popularity because it can be operated with minimal input from the local operator, be serviced and maintained by a roving technician under contract, and can also be operated remotely with the aid of telemetry. Some of these technologies are also packaged in such a way that it largely eliminates the use of chemicals, contains one or more treatment barriers, have automated cleaning regimes, can operate by gravity alone and therefore obviate the need for electricity, and can be pre-manufactured and packaged on a skid-mount or in a container.

For decentralised treatment systems, the use of automated more sophisticated systems operated and maintained under contract by reputable water treatment companies are therefore likely to present a “best” treatment option in terms of performance, compliance and sustainability.

Costs

- Centralized water treatment plants cost around $700 per family, making them prohibitively expensive for developing countries to build.

Acknowledgements

- J.M. Arnalà , B. Garcia-Fayos, G. Verdu, J. Lora. Ultrafiltration as an alternative membrane technology to obtain safe drinking water from surface water: 10 years of experience on the scope of the AQUAPOT project. Polytechnic University of Valencia, Chemical and Nuclear Engineering Department, Camino de Vera s/n 46022 Valencia, Spain. May 2008.

- Swartz, Christian D. A PLANNING FRAMEWORK TO POSITION RURAL WATER TREATMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA FOR THE FUTURE. WRC, 2009.